If there’s one thing Andy Stout took from the D.C. punk scene, it’s a do-it-yourself ethos. The musician discovered the underground movement as a teenager in Greencastle, Pennsylvania, a small, rural town just 10 minutes away from the Maryland border.

If there’s one thing Andy Stout took from the D.C. punk scene, it’s a do-it-yourself ethos. The musician discovered the underground movement as a teenager in Greencastle, Pennsylvania, a small, rural town just 10 minutes away from the Maryland border.

“Growing up in Greencastle, there wasn’t a lot going on,” Stout said.

So he and his friends created a proximate scene in their own hometown.

“As a burgeoning juvenile delinquent, you meet other juvenile delinquents and skateboard and form bands and create fan zines,” added Stout, who now lives and works in Frederick. “It’s funny how popular all of this is now, because back when it was happening, this was definitely not the mainstream. It was an empowering thing because you saw these kids in D.C. doing it and you realized, ‘Oh, I can do this, too.’”

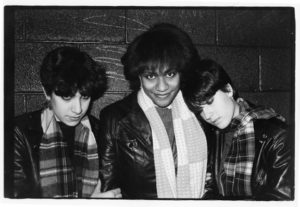

Some of his friends even moved to the city to play, where their pictures were captured by artist and photographer Cynthia Connolly. She published the photos in a groundbreaking book called “Banned in DC,” a collection of stories, flyers, and pictures from the scene’s formative years. Connolly herself had been involved in the D.C. punk movement since 1981, and embraced the same DIY attitude as Stout. From 1979 to 1985, punk was incredibly active yet virtually ignored by most of the city, she said. Radio stations didn’t play local bands. Newspapers didn’t review them. Dischord Records, a seminal punk label, was started by members of The Teen Idles just so the band could release an EP.

“That’s kind of how I got the title,” she said. “We weren’t literally banned, but we didn’t have any community support. And in a way, that neglect inspired us to be even more aggressive. It gave us a sense of pride because whenever we had success, it was because we did the work.”

Connolly will share more stories from the D.C. punk scene Saturday at New Spire Arts, where Stout invited her to present a retrospective on the book. “Banned in DC” obviously still resonates with people like him (Stout can remember convincing older friends to drive him into the city for shows), but the D.C. scene also had an impact nationally and internationally. Dischord Records went on to release albums from bands like Minor Threat and Fugazi, local acts with an outsized influence on the broader punk movement. Venues like Madams Organ — originally an artist’s co-op, without the apostrophe — played host to touring punk groups like D.O.A and The Penetrators. Stout thinks the tenacity of D.C. musicians continues to influence new art movements.

“It was the foundation of youth culture in the U.S.,” he said. “You see kids starting their own bands, starting their own zines, creating their own music scenes, and it can all be traced back to punk in D.C.”

At the very least, the scene continues to inspire local artists. D.C. filmmaker James June Schneider will also be at New Spire on Saturday to preview his upcoming documentary, “Punk the Capital,” a look at the nascent days of the city’s punk underground. The movement catalyzed Stout to bring major shows to the Frederick area, as well. In 1998, he managed to book Fugazi at the 180 Club in Hagerstown, selling hundreds of tickets in a matter of minutes. Admittedly, there was a personal benefit. Stout was in the band that opened the concert, Miss Lonelyheart, sharing the stage with — in his words — “one of the most legendary rock bands of our generation.”

For Connolly, the punk scene still ties to larger social movements, part of the book’s enduring appeal. In a new afterword, she describes the movement as a reaction to the conservatism of the Reagan era, and — at least partly — a feminist response to mainstream rock music. She was first drawn to punk as the antithesis of the surfer scene in her hometown of Los Angeles, where bands like Led Zeppelin and AC/DC were perennially popular and perennially reduced women to groupies or sex objects.

But punk had badass performers like Patti Smith and Joan Jett, making room for other women to join the fray. In D.C., Madams Organ was started by three female students from the Corcoran College of the Arts and Design. Connolly — another Corcoran graduate — played her own important role, photographing the scene and designing the cover art for Minor Threat’s EP, “Out of Step.”

Of course, she understands that the popularity of “Banned in DC” is also inextricably tied to its early photos of bands like Bad Brains and Fugazi — bands that later became internationally famous. But it wasn’t those groups, or any specific group, that encouraged her to spend two years working on the book.

“The story isn’t about bands becoming famous,” she said. “The story is about a small group of people who had the energy and the motivation to create a community of their own. And how we made history, just by documenting and sharing it.”